Resistance Dignity and Pride African American Art in Los Angeles

Stereotypes of African Americans and associated with their culture have evolved within American society dating back to the slavery of black people during the colonial era. These stereotypes are largely continued to the persistent racism and discrimination faced past African Americans residing in the The states.

Nineteenth-century minstrel shows used white actors in blackface and attire supposedly worn past African-Americans to lampoon and disparage blacks. Some nineteenth century stereotypes, such as the sambo, are now considered to be derogatory and racist. The "Mandingo" and "Jezebel" stereotypes sexualizes African-Americans as hypersexual. The Mammy archetype depicts a motherly blackness woman who is dedicated to her part working for a white family, a stereotype which dates back to Southern plantations. African-Americans are oft stereotyped to accept an unusual ambition for fried chicken, watermelon, and grape potable.

In the 1980s and following decades, emerging stereotypes of blackness men depicted them as drug dealers, scissure addicts, hobos, and subway muggers.[1] Jesse Jackson said media portray blacks equally less intelligent.[2] The magical Negro is a stock character who is depicted equally having special insight or powers, and has been depicted (and criticized) in American cinema.[3] In recent history, Black men are stereotyped to be deadbeat fathers.[iv]

Stereotypes of black women include beingness depicted as welfare queens or as angry black women who are loud, ambitious, demanding, and rude.[5]

Historical stereotypes [edit]

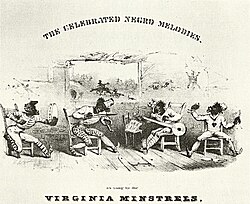

Detail from cover of The Celebrated Negro Melodies, every bit Sung by the Virginia Minstrels, 1843

Minstrel shows portrayed and lampooned blacks in stereotypical and ofttimes disparaging ways, every bit ignorant, lazy, buffoonish, superstitious, joyous, and musical. Greasepaint was a way of theatrical makeup popular in the Us, which was used to event the countenance of an iconic, racist American classic: that of the "darky" or "coon" (both are racial slurs). White blackface performers used to use burnt cork and later greasepaint or shoe shine to blacken their skin and exaggerate their lips, frequently wearing woolly wigs, gloves, tailcoats, or ragged clothes to complete the transformation.

This reproduction of a 1900 William H. Westward minstrel evidence affiche, originally published past the Strobridge Litho Co., shows the transformation from "white" to "blackness."

The best-known such stock character is Jim Crow, featured in innumerable stories, minstrel shows, and early on films. Many other stock characters are popularly known besides, such as Mammy and Jezebel. The stock characters are notwithstanding continuously used and referenced for a number of dissimilar reasons. Many articles reference Mammy and Jezebel in television shows with black female master characters, every bit in the idiot box series Scandal.

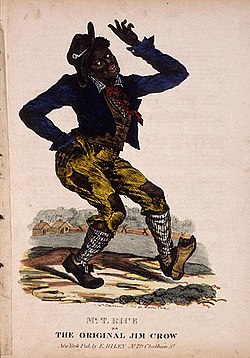

Jim Crow [edit]

The character Jim Crow was dressed in rags, battered hat, and torn shoes. The actor blackened his face and hands and impersonated a very nimble and irreverently witty African-American field manus who sang, "Plow near and wheel about, and exercise simply and then. And every time I plow near I Jump Jim Crow."

Sambo, Golliwog, and pickaninny [edit]

The Sambo stereotype gained notoriety through the 1898 children's volume The Story of Little Black Sambo by Helen Bannerman. Information technology told the story of a boy named Sambo who outwitted a group of hungry tigers. "Sambo" refers to black men who were considered very happy, ordinarily laughing, lazy, irresponsible, or carefree. That delineation of black people was displayed in films of the early on 20th century. The original text suggested that Sambo lived in India, but that fact may have escaped many readers. The book has oft been considered to be a slur confronting Africans.[vi]

Golliwog is a similarly enduring extravaganza, nearly oftentimes represented equally a blackface doll, and dates to American children'south books of the late 19th century. The character found great popularity among other Western nations, with the Golliwog remaining popular well into the twentieth century. Notably, as with Sambo, the term equally an insult crosses ethnic lines. The derived Commonwealth English language epithet "wog" is applied more frequently to people from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian subcontinent than to African-Americans, but "Golly dolls" all the same in production mostly retain the expect of the stereotypical blackface minstrel.[ citation needed ]

The term pickaninny, reserved for children, has a similarly broadened blueprint of use. Information technology originated in a Portuguese word for small kid in general, but information technology was applied particularly to African-American children in the United States and afterward to Australian Aboriginal children. Although not unremarkably used alone as a character name, the pickaninny became a mainstream stock character in white-dominated fiction, music, theater, and early film in the United States and across.[ citation needed ]

Black children every bit alligator allurement [edit]

Racist 1900s postcard, captioned: "Alligator bait, Florida"

A variant of the pickaninny stereotype depicted black children being used as bait to chase alligators. This motif was featured in postcards, souvenirs, advertisements, and other artifacts of popular civilization.[7] Although scattered references to the supposed do appeared in early 20th-century newspapers, there is no credible evidence that the stereotype reflected an actual historical practise.[viii]

In 2020, the University of Florida banned the phrase "Gator Bait" as a cheer at Florida Gators sporting events due to the phrase's racist associations.[nine]

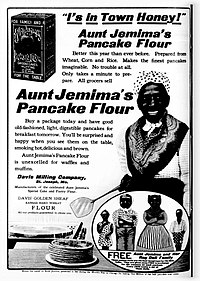

Mammy [edit]

Clipping from May 29, 1910, result of the Chicago Tribune reporting a movement to build a "monument" to "Ol' Blackness Mammy" in Washington, D.C. The subhead mentions "the sentiment that clings to this picturesque character of antebellum days."

Early accounts of the Mammy archetype come from memoirs and diaries that emerged after the American Ceremonious War describing African-American women household slaves who served as nannies giving maternal care to the white children of the family unit and receiving an unusual degree of trust and affection from their enslavers. The personal accounts idealized the role of the dominant female house slave: a woman completely dedicated to the white family, peculiarly the children, and given consummate charge of domestic management. She was a friend and advisor.[10]

Mandingo [edit]

The Mandingo is a stereotype of a sexually voracious black homo with a huge penis,[11] invented by white slave owners to promote the notion that blacks were non civilizable but "animalistic" past nature. They asserted, for example, that in "Negroes all the passions, emotions, and ambitions, are almost wholly subservient to the sexual instinct" and "this structure of the oversexed blackness male parlayed perfectly into notions of black bestiality and primitivism."[12]

The term mandingo is of 20th century origin.[13]

Sapphire [edit]

The Sapphire stereotype is a domineering female who consumes men and usurps their office.[14] She was characterized as a stiff, masculine workhorse who labored with black men in the fields or an aggressive woman, whose overbearing drove away her children and partners.[15] Her assertive demeanor is like to the Mammy but without maternal compassion and understanding.[xv]

1 social scientist has claimed that black women'southward matriarchal status, rather than discriminatory social and economic policies, was responsible for social pathologies in black families.[16]

Jezebel [edit]

The Jezebel, a stereotype of a sexually voracious, promiscuous black woman, was the counterimage of the demure Victorian lady in every manner.[17] The idea stemmed from Europeans' first meet with seminude women in tropical Africa.[17] The African practice of polygamy was attributed to uncontrolled lust, and tribal dances were construed as pagan orgies, in contrast to European Christian guiltlessness.[17]

The supposed indiscriminate sexual appetite of black women slaves justified their enslavers' efforts to brood them with other slaves.[18] Information technology also justified rape by white men, even as a legal defense. Black women could not be rape victims considering they "always desired sex."[19] [20] The abolitionist James Redpath wrote that slave women were "gratified by the criminal advances of Saxons."[21] [ description needed ] During and after Reconstruction, "Blackness women... had petty legal recourse when raped by white men, and many Black women were reluctant to written report their sexual victimization by Black men for fright that the Blackness men would exist lynched."[22] [23]

The Jezebel stereotype contrasts with the Mammy stereotype, providing two broad categories for pigeonholing by whites.[24]

Tragic mulatta [edit]

A stereotype that was popular in early on Hollywood, the "tragic mulatta," served every bit a cautionary tale for black people. She was ordinarily depicted as a sexually attractive, light-skinned woman who was of African descent simply could laissez passer for Caucasian. The stereotype portrayed light-skinned women equally obsessed with getting ahead, their ultimate goal being marriage to a white, middle-class human. The only route to redemption would be for her to accept her "blackness."

An instance of the "tragic mulatta" tin be found in the 1933 novel Imitation of Life and its 1934 and 1959 movie adaptations. The "tragic mulatta" is depicted every bit mean and unsympathetic, simply her "mammy" counterpart is presented as a positive role model.[25] The 2014 satirical film Dear White People has the protagonist fall into and and then subvert the stereotype, and the secondary characters explore other blackness stereotypes.[ commendation needed ]

Uncle Tom [edit]

The Uncle Tom stereotype, from the title character of the novel Uncle Tom'south Cabin, represents a black man who is mayhap elementary-minded and compliant just near essentially interested in the welfare of whites over that of other blacks. Synonyms include "sellout" and the derisive "house Negro." In contemporary slang, the male person version of Aunt Jemima.[ citation needed ]

Black brute, Black Cadet [edit]

Black men are stereotyped to exist cruel, animalistic, subversive, and criminal. Black brutes or black bucks are depicted as hideous, terrifying black male predators who target helpless victims, particularly white women.[26]

In the mail-Reconstruction United States, Black Buck was a racial slur used to describe a certain blazon of African American homo. In particular, the caricature was used to describe black men who refused to bend to the law of white authority and were seen every bit irredeemably violent, rude, and lecherous.

In art [edit]

A comprehensive examination of the restrictions imposed upon African Americans in the United States by culture is examined by the fine art historian Guy C. McElroy in the catalog to the exhibit "Facing History: The Black Paradigm in American Art 1710–1940." According to McElroy, the artistic convention of representing African Americans as less than fully realized humans began with Justus Engelhardt Kühn's colonial-era painting Henry Darnall Iii equally a kid.[27] Although Kühn's piece of work existed "simultaneously with a radically different tradition in colonial America," as indicated by the work of portraitists such as Charles (or Carolus) Zechel, the market need for such work reflected the attitudes and the economic status of their audience.

From the Colonial Era to the American Revolution, ideas most African Americans were variously used in propaganda either for or against slavery. Paintings like John Singleton Copley's Watson and the Shark (1778) and Samuel Jennings's Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences (1792) are early on examples of the debate nether fashion at that fourth dimension equally to the function of blackness people in America. Watson represents an historical event, but Freedom is indicative of abolitionist sentiments expressed in Philadelphia's post-revolutionary intellectual community. Notwithstanding, Jennings' painting represents African Americans in a stereotypical role as passive, submissive beneficiaries of not merely slavery's abolition merely also knowledge, which liberty had graciously bestowed upon them.

As some other stereotypical extravaganza "performed by white men bearded in facial paint, minstrelsy relegated black people to sharply divers dehumanizing roles." With the success of T. D. Rice and Daniel Emmet, the label of "blacks equally buffoons" was created.[27] One of the earliest versions of the "black as buffoon" tin be seen in John Lewis Krimmel'due south Quilting Frolic. The violinist in the 1813 painting, with his tattered and patched wearable, along with a bottle protruding from his coat pocket, appears to be an early model for Rice's Jim Crow character. Krimmel's representation of a "[s]habbily dressed" fiddler and serving girl with "toothy smile" and "oversized red lips" marks him as "...one of the first American artists to employ physiognomical distortions equally a basic element in the delineation of African Americans."[27]

Contemporary stereotypes [edit]

Crack addicts and drug dealers [edit]

Scholars concord that news-media stereotypes of people of color are pervasive.[28] [29] [xxx] [31] [32] [33] African Americans were more likely to appear every bit perpetrators in drug and violent law-breaking stories in the network news.[34]

In the 1980s and the 1990s, stereotypes of black men shifted and the main and common images were of drug dealers, scissure victims, the underclass and impoverished, the homeless, and subway muggers.[1] Similarly, Douglas (1995), who looked at O. J. Simpson, Louis Farrakhan, and the One thousand thousand Homo March, found that the media placed African-American men on a spectrum of practiced versus evil.

Watermelon and fried chicken [edit]

A postcard showing an African-American girl eating a large watermelon.

At that place are commonly held stereotypes that African Americans have an unorthodox appetite for watermelons and love fried craven. Race and folklore professor Claire Schmidt attributes the latter both to its popularity in Southern cuisine and to a scene from the film Birth of a Nation in which a rowdy African-American homo is seen eating fried chicken in a legislative hall.[35]

Welfare queen [edit]

The long-lived stereotype depicts an African-American woman who defrauds the public welfare system for a life of idle luxury. Studies show its roots in both race and gender. Franklin Gilliam, the author of a public perception experiment on welfare, concludes:

While poor women of all races get blamed for their impoverished status, African-American women are seen to commit the most egregious violations of American values. This story line taps into stereotypes about both women (uncontrolled sexuality) and African Americans (laziness).

Studies show that the public dramatically overestimates the number of African Americans who live beneath the poverty line (less than a quarter, compared with the national average around 15%), a misperception attributed to media portrayals.[36]

Magical Negro [edit]

The magical Negro (or mystical Negro) is a stock character who appears in a variety of fiction and uses special insight or powers to help the white protagonist. The word "Negro", at present considered archaic and offensive by some.[iii]

The term was mentioned by Spike Lee, who dismissed the archetype of the "super-duper magical Negro" in 2001 while discussing films with students at Washington State University[38] and at Yale University.[39] The Magical Negro is a subtype of the more generic numinous Negro, a term coined past Richard Brookhiser in National Review.[40] The latter term refers to clumsy depictions of saintly, respected or heroic black protagonists or mentors in The states amusement.[40]

Angry black woman [edit]

In the 21st century, the "aroused black woman" is depicted equally loud, aggressive, enervating, uncivilized, and physically threatening, as well as lower-centre-class and materialistic.[5] She will not stay in what is perceived every bit her "proper" identify.[41]

Controlling image [edit]

Controlling images are stereotypes that are used against a marginalized grouping to portray social injustice as natural, normal, and inevitable.[42] By erasing their individuality, controlling images silence blackness women and make them invisible in lodge.[5] Jones et al. stated that, in 1851, Sojourner Truth, a black female civil rights advocate, disrupted and ultimately saved a Women'southward Rights Convention when she asked, "Ain't I a Woman?".[41] Jones et al. argued that the statement challenged white women to recollect nigh how they experienced womanhood differently from how blackness women and added, "Sojourner revealed that arguments used to subordinate white women were different from and at times contradicted by arguments that were used to subordinate black women."[41]

Jones et al. stated that while the experience of womanhood differs from ethnicity to ethnicity: "Sojourner exercised her powerful voice to betrayal and to resist: (ane) the prioritization of white women's needs; and (2) the assumption that white women's experiences stand for the experiences of all women, when in fact they do not."[41] The controlling image present is that white women are the standard for everything, even oppression, which is merely false.[41]

Education [edit]

Studies show that scholarship has been dominated by white men and women.[43] Existence a recognized academic includes social activism as well equally scholarship. That is a hard position to hold since white counterparts dominate the activist and social work realms of scholarship.[43] It is notably difficult for a black woman to receive the resources needed to consummate her research and to write the texts that she desires.[43] That, in part, is due to the silencing effect of the angry blackness woman stereotype. Black women are skeptical of raising bug, also seen as complaining, within professional person settings because of their fear of being judged.[5]

Mental and emotional consequences [edit]

Because of the aroused black woman stereotype, black women tend to become desensitized virtually their ain feelings to avoid judgment.[44] They often feel that they must show no emotion outside of their comfy spaces. That results in the accumulation of these feelings of hurt and can be projected on loved ones as acrimony.[44] Once seen every bit angry, black women are ever seen in that low-cal and then take their opinions, aspirations, and values dismissed.[44] The repression of those feelings can too result in serious mental health issues, which creates a circuitous with the strong black woman. As a common problem within the blackness community, black women and men seldom seek assist for their mental health challenges.[ citation needed ]

Interracial relationships [edit]

Oftentimes, black women's opinions are not heard in studies that examine interracial relationships.[45] Black women are oft assumed to be but naturally angry. However, the implications of black women's opinions are non explored within the context of race and history. According to Erica Child's written report, blackness women are about opposed to interracial relationships.[45]

Since the 1600s, interracial sexuality has represented unfortunate sentiments for black women.[45] Black men who were engaged with white women were severely punished.[45] However, white men who exploited black women were never reprimanded. In fact, information technology was more economically favorable for a black woman to birth a white man'south child because slave labor would be increased by the 1-drib rule. Information technology was taboo for a white woman to have a black man's child, every bit it was seen every bit race tainting.[45] In gimmicky times, interracial relationships can sometimes represent rejection for black women. The probability of finding a "skilful" black man was low because of the prevalence of homicide, drugs, incarceration, and interracial relationships, making the task for black women more than hard.[45]

As concluded from the study, interracial dating compromises blackness dear.[45] It was often that participants expressed their opinions that blackness love is important and represents more than the artful since information technology is about black solidarity.[45] "Angry" blackness women believe that if whites will never understand blackness people and they nevertheless regard black people every bit junior, interracial relationships will never exist worthwhile.[45] The written report shows that nearly of the participants remember that blackness women who take interracial relationships volition not beguile or disassociate with the black community, but black men who date interracially are seen as taking abroad from the black community to advance the white patriarchy.[45]

"Black bitch" [edit]

Only as the "aroused black woman" is a gimmicky manifestation of the Sapphire stereotype, the "black bitch" is a gimmicky manifestation of the Jezebel stereotype. Characters termed "bad blackness girls," "black whores," and "blackness bitches" are archetypes of many blaxploitation films produced by the Hollywood establishment. One example of the archetype is the character of Leticia Musgrove in the picture show Monster's Ball, portrayed by Halle Drupe.

Journalists utilized the angry blackness adult female archetype in their narratives of Michelle Obama during the 2007–2008 presidential primaries. Coverage of her ran the gamut from fawning to favorable to stiff to aroused to intimidating and unpatriotic. She told Gayle King on CBS This Forenoon that she has been caricatured as an "angry blackness woman" and that she hopes America will one day learn more about her. "That'south been an image that people have tried to paint of me since, you know, the mean solar day Barack announced, that I'm some angry blackness woman," she said.[46]

She dismissed a book by New York Times reporter Jodi Kantor entitled The Obamas. Kantor portrayed her every bit a difficult-nosed operator who sometimes clashed with staffers, but she insisted that the portrayal is inaccurate.[47]

Strong black woman [edit]

The "strong black woman" stereotype is a discourse through that primarily black middle-class women in the blackness Baptist Church instruct working-class blackness women on morality, self-assist, and economic empowerment and assimilative values in the bigger interest of racial uplift and pride (Higginbotham, 1993). In that narrative, the woman documents eye-course women attempting to push back against ascendant racist narratives of black women beingness immoral, promiscuous, unclean, lazy and mannerless by engaging in public outreach campaigns that include literature that warns confronting brightly colored clothing, gum chewing, loud talking, and unclean homes, among other directives.[48] That discourse is harmful, dehumanizing, and silencing.

Corbin et al. argued, "We see STRONGBLACKWOMAN equally a dominant response that preserves individual agency and staves off being maligned and dismissed every bit an Angry Blackness Woman in places where being heard is critically important. It becomes part of a counteroffensive script to cope with misogynoir attacks. Additionally, STRONGBLACKWOMAN functions every bit an internalized mechanism that privileges resilience, perseverance, and silence."[48]

The "strong black woman" narrative is another decision-making image that perpetuates the idea that it is adequate to mistreat black women because they are strong and so can handle information technology. That narrative can also act as a silencing method. When blackness women are struggling to be heard because they go through things in life like everyone else, they are silenced and reminded that they are potent, instead of actions being taken toward alleviating their problems.[48]

Contained black woman [edit]

The "independent black woman" is the depiction of a narcissistic, overachieving, financially successful woman who emasculates black males in her life.[47] Mia Moody, a professor of journalism at Baylor University, described the "independent blackness woman" in two articles: "A rhetorical assay of the significant of the 'independent woman'"[49] and "The meaning of 'Independent Woman' in music."[l]

In her studies, Moody concluded that the lyrics and videos of male and female artists portrayed "independent women" differently. The rapper Roxanne Shanté's 1989 rendition of "Independent Woman" explored relationships and asked women not to dote on partners who do not reciprocate. Similarly, the definition of an "contained woman" in Urban Dictionary is this: "A woman who pays her own bills, buys her own things, and does non permit a man to affect her stability or self-conviction. She supports herself entirely on her own and is proud to be able to do so." Destiny'due south Child'due south vocal "Contained Women" encourages women to exist strong and independent for the sake of their nobility and not for the sake of impressing men. The grouping frowns upon the idea of depending on anyone: "If y'all're gonna brag, brand sure information technology'due south your coin you flaunt/depend on no one else to give you what yous want". The singers claim their independence through their fiscal stability.[49] [50]

Moody concluded female rappers often depicted sex activity as a tool for obtaining independence by controlling men and buying material goods. While male rappers viewed the independent woman as ane who is educated, pays her own bills, and creates a good home life, they neglect to mention settling downwardly and often annotation that a woman should non weigh them down. Moody analyzed songs, corresponding music videos, and viewer comments of half-dozen rap songs by Yo Gotti, Webbie, Drake, Candi Redd, Trina, and Nicki Minaj. She found four principal letters: wealth equals independence, beauty and independence are connected, boilerplate men deserve perfect women, and sexual prowess equals independence.[49] [50]

Black American princess [edit]

Athleticism [edit]

Blacks are stereotyped as beingness more than athletic and superior at sports than other races. Even though they make up merely 12.4 percent of the Usa population, 75% of NBA players[51] and 65% of NFL players are black.[52] Until 2010, all sprinters who had broken the 10-second barrier in the 100 meter dash were black.[ citation needed ] African-American college athletes may be seen every bit getting into college solely on their athletic ability, non their intellectual and bookish merit.[53]

Blackness athletic superiority is a theory that says blacks possess traits that are caused through genetic and/or environmental factors that permits them to excel over other races in athletic competition. Whites are more than likely to hold such views, but some blacks and other racial affiliations exercise as well.[54] [55] [56] A 1991 poll in the Us indicated that one-half of the respondents agreed with the conventionalities that "blacks take more natural physical ability."[57]

In a 1997 study on racial stereotypes in sports, participants were shown a photograph of a white or a blackness basketball role player. They and then listened to a recorded radio broadcast of a basketball. White photographs were rated as exhibiting significantly more intelligence in the way they played the game, but the radio circulate and the target player represented past the photograph were the aforementioned throughout the trial.[58] Several other authors have said that sports coverage that highlights "natural black athleticism" has the consequence of suggesting white superiority in other areas, such every bit intelligence.[59] The stereotype suggests that African Americans are incapable of competing in "white sports" such every bit ice hockey and swimming.[lx] [61] [62] [63] [64] [65] [66] [67] [68]

Intelligence [edit]

In 1844, Secretary of State John C. Calhoun, arguing for the extension of slavery, said, "Here [scientific confirmation] is proof of the necessity of slavery. The African is incapable of self care and sinks into lunacy under the burden of freedom. It is a mercy to give him the guardianship and protection from mental death."[69]

Even afterward slavery concluded, the intellectual chapters of black people was still frequently questioned. Lewis Terman wrote in The Measurement of Intelligence in 1916:

[Black and other indigenous minority children] are ineducable across the nearest rudiments of preparation. No amount of schoolhouse pedagogy will ever make them intelligent voters or capable citizens in the sense of the world... their dullness seems to be racial, or at to the lowest degree inherent in the family stock from which they come up....

Terman advocated racial segregation:

Children of this grouping should be segregated in special classes and exist given pedagogy which is concrete and practical. They cannot main abstractions, simply they can be made efficient workers....

As well, he made statements supporting eugenics:

There is no possibility at nowadays of convincing society that they should not be allowed to reproduce, although from a eugenic indicate of view they constitute a grave problem because of their unusual prolific convenance.

Ane media survey in 1989 showed that blacks were more likely than whites to be described in demeaning intellectual terms.[70] The political activist and presidential candidate Jesse Jackson said in 1985 that the news media portray blacks as less intelligent than they are.[two] The motion picture director Spike Lee explains that the images have negative impacts: "In my neighborhood, we looked upwardly to athletes, guys who got the ladies, and intelligent people." Images widely portrayed black Americans equally living in inner-city areas, very low-income and less educated than whites.

Stephen Jay Gould'south book The Mismeasure of Man (1981) demonstrated how early 20th-century biases among scientists and researchers affected their purportedly objective scientific studies, information gathering, and conclusions which they drew about the accented and relative intelligence of different groups and of gender and intelligence.

Even so-called positive images of blacks can lead to stereotypes almost intelligence. In Darwin'due south Athletes: how sport has damaged Black America and preserved the myth of race, John Hoberman writes that the prominence of African-American athletes encourages a lack of emphasis on bookish achievement and merit in black communities.[71]

Media [edit]

Early stereotypes [edit]

Early minstrel shows of the mid-19th century lampooned the supposed stupidity of blackness people.[ commendation needed ] Fifty-fifty later slavery ended, the intellectual capacity of blackness people was still frequently questioned. Movies such as Nativity of a Nation (1915) questioned whether black people were fit to run for governmental offices or to vote.

Some critics have considered Marker Twain'due south Adventures of Huckleberry Finn as racist because of its depiction of the slave Jim and other black characters. Some schools have excluded the book from their curricula or libraries.[72]

Stereotypes pervaded other aspects of culture, such equally various lath games that used Sambo or similar imagery in their design. An example is the Jolly Darkie Target Game in which players were expected to toss a ball through the "gaping oral cavity" of the target in cardboard decorated using imagery of Sambo.[73]

Film and television [edit]

The political activist and quondam presidential candidate Jesse Jackson said in 1985 that the news media portrayed black people as "less intelligent than we are."[74] Sometime Ground forces Secretary Clifford Alexander, testifying before the Senate Cyberbanking, Housing and Urban Affairs Commission in 1991, said, "You meet u.s. as less than you are. You think that we are non equally smart, not as energetic, not as well suited to supervise you as you are to supervise u.s..... These are the ways y'all perceive us, and your perceptions are negative. They are fed by motion pictures, ad agencies, news people and tv."[75] The film director Spike Lee explains that the images have negative impacts: "In my neighborhood, we looked up to athletes, guys who got the ladies, and intelligent people," said Lee. "[Now] If you're intelligent, you're called a white guy or girl."[76]

In film, black people are likewise shown in a stereotypical fashion that promotes notions of moral inferiority. In terms of female person movie characters shown by race:[77]

- Using vulgar profanity: blacks 89%, whites 17%

- Beingness physically violent: blacks 56%, whites 11%

- Defective self-control: blacks 55%, whites six%

African-American women take been represented in picture and idiot box in a diverseness of unlike ways, starting from the stereotype/classic of "mammy" (as is exemplified the office played by Hattie McDaniel in Gone with the Current of air) drawn from minstrel shows,[78] through to the heroines of blaxploitation movies of the 1970s, just the latter was then weakened past commercial studios.[79] The mammy stereotype was portrayed as asexual while later representations of black women demonstrated a predatory sexuality.[80]

Fashion [edit]

In print, blackness people are portrayed every bit overtly aggressive. In a study of manner magazine photographs, Millard and Grant institute that black models are frequently depicted equally more aggressive and sociable merely less intelligent and achievement-oriented.[81]

Sports [edit]

In Darwin'southward Athletes, John Hoberman writes that the prominence of African-American athletes encourages a lack of emphasis on bookish achievement in blackness communities.[71] Several other authors have said that sports coverage that highlights "natural black athleticism" has the effect of suggesting white superiority in other areas, such as intelligence.[82] Some contemporary sports commentators take questioned whether blacks are intelligent enough to hold "strategic" positions or coach games such as football.[83]

In another case, a written report of the portrayal of race, ethnicity, and nationality in televised sporting events by the journalist Derrick Z. Jackson in 1989 showed that blacks were more likely than whites to be described in demeaning intellectual terms.[84]

Criminal stereotyping [edit]

According to Lawrence Grossman, one-time president of CBS News and PBS, tv newscasts "disproportionately show African Americans under arrest, living in slums, on welfare, and in need of help from the community."[85] [86] Similarly, Hurwitz and Peffley wrote that violent acts committed by a person of color often accept up more one-half of local news broadcasts, which ofttimes portray the person of color in a much more than sinister light than their white counterparts. The authors argue that African Americans are non only more probable to be seen equally suspects of horrendous crimes in the press but likewise are interpreted as existence violent or harmful individuals to the general public.[87] [ folio needed ]

Mary Beth Oliver, a professor at Penn Country Academy, stated that "the frequency with which black men specifically accept been the target of police assailment speaks to the undeniable role that race plays in false assumptions of danger and misdeed."[88] Oliver additionally stated that "the variables that play contributory roles in priming thoughts of dangerous or aggressive black men, are age, dress, and gender, amongst others which lead to the imitation assumptions of danger and criminality."[88]

New media stereotypes [edit]

[edit]

In 2012, Mia Moody, assistant professor of journalism, public relations and new media in Baylor'south College of Arts and Sciences, documented Facebook fans' utilize of social media to target U.s.a. President Barack Obama and his family unit through stereotypes. Her study plant several themes and missions of groups targeting the Obamas. Some groups focused on attacking his politics and consisted of Facebook members who had an interest in politics and used social media to share their ideas. Other more-malicious types focused on the president's race, religion, sexual orientation, personality, and diet.[89]

Moody analyzed more than than 20 Facebook groups/pages using the keywords "hate," "Barack Obama," and "Michelle Obama." Hate groups, which once recruited members through word of mouth and distribution of pamphlets, spread the message that one race is inferior, targeted a historically oppressed group, and used degrading, hateful terms.[89]

She concluded that historical stereotypes focusing on diet and blackface had all just disappeared from mainstream tv shows and movies, but had resurfaced in newmedia representations. Most portrayals brutal into iii categories: blackface, animalistic and evil/angry. Similarly, media had made progress in their handling of gender-related topics, but Facebook offered a new platform for sexist messages to thrive. Facebook users played upward shallow, patriarchal representations of Michelle Obama, focusing on her emotions, appearance, and personality. Conversely, they emphasized historical stereotypes of Barack Obama that depicted him as flashy and animalistic. Media'southward reliance on stereotypes of women and African Americans not merely hindered civil rights but also helped determine how people treated marginalized groups, her study found.[89]

Video games [edit]

Representations of African Americans in video games tend to reinforce stereotypes of males equally athletes or gangsters.[90] [91]

Hip hop music [edit]

Hip hop music has reinforced stereotypes about black men. Violent, misogynistic lyrics in rap music performed by African American male person rappers has increased negative stereotypes against black men.[92] African-American women are degraded and referred to as "bitches" and "hoes" in rap music.[93] African-American women are over-sexualized in hip hop music videos and are portrayed as sexual objects for rappers.[94] Hip hop portrays a stereotypical blackness masculine aesthetic.[95]

Hip hop has stereotyped Black men as hypersexual thugs and gangsters who hail from a inner urban center ghetto.[96]

Meet as well [edit]

- African characters in comics

- African-American culture

- African-American representation in Hollywood

- Afrophobia

- Black matriarchy

- Colored people'southward time

- Coon vocal

- How Rastus Gets His Turkey

- Life as a BlackMan (board game)

- Racial profiling

- Scientific racism

- Stepin Fetchit

- Criminal stereotype of African Americans

- Uncle Remus

- Stereotypes of groups within the United States

- Stereotypes of Americans

- Stereotypes of Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States

- Stereotypes of white Americans

- Stereotypes of East Asians in the U.s.a.

- Stereotypes of indigenous peoples of Canada and the United States

- Stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims in the United States

- Stereotypes of Jews

- Ethnic stereotype

- Racism against Black Americans

- Racism in the United States

- Racialization

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b Drummond, William J. "About Face up: From Alliance to Alienation. Blacks and the News Media". (1990) The American Enterprise

- ^ a b Jackson Assails Press On Portrayal of Blacks (NYT)

- ^ a b D. Marvin Jones (2005). Race, Sex, and Suspicion: The Myth of the Black Male person . Praeger Publishers. p. 35. ISBN978-0-275-97462-6.

- ^ https://apnews.com/commodity/725a00fbc56d4e71a2f66bae776cabed

- ^ a b c d Harris-Perry, Melissa (2011). Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America. Yale Academy Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN978-0-300-16554-8.

- ^ The Picaninny Caricature Archived 2011-05-01 at the Wayback Machine, Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University.

- ^ Rank, Scott Michael, ed. (20 July 2012). "The Coon Extravaganza: Coons equally Alligator Bait". History on the Internet . Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Emery, David (9 June 2017). "Were black children used as alligator bait in the American South?". Snopes . Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Adelson, Andrea (eighteen June 2020). "Florida putting end to 'Gator Allurement' cheer, band performance due to racist history of term". ESPN . Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ White 1999, p. 49

- ^ Davis, Gary L.; Cross, Herbert J. (1979). "Sexual stereotyping of Black males in interracial sex". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 8 (3): 269–279. doi:x.1007/bf01541243. PMID 485815. S2CID 2097117.

- ^ "J. A. Rogers, 3 Sex and Race 150 (1944)" (PDF). harvard.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Van Deburg, William 50. (1984). Slavery and Race in American Popular Culture. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 149. ISBN978-0-299-09630-4.

- ^ White 1999, p. 176

- ^ a b West 2008, p. 289

- ^ West 2008, p. 296

- ^ a b c White 1999, p. 29

- ^ Collins 1990, p. 89

- ^ West 2008, p. 294

- ^ Collins 1990, p. 91

- ^ Redpath, James (1859). The Roving Editor: Or, Talks with Slaves in the Southern States. A. B. Burdick. p. 141.

- ^ Leiter, Andrew (2010). In the Shadow of the Black Brute. LSU Press. pp. 176, 38, 220, four, 33. ISBN978-0-8071-3753-6.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 . Harper & Row. pp. 427, 430–31. ISBN978-0-06-091453-0.

- ^ Rojas, Maythee (2009). Women of color and feminism. Berkeley, Calif.: Seal Press. p. 35. ISBN978-1-58005-272-6.

- ^ Kretsedemas, Philip (21 January 2010). ""But She's Non Black!" Viewer Interpretations of "Angry Black Women" on Prime Time Telly". Journal of African American Studies. 14 (2): 149–170. doi:10.1007/s12111-009-9116-3. S2CID 142722769.

- ^ "The Brute Extravaganza - Jim Crow Museum - Ferris State Academy".

- ^ a b c McElroy, Guy C.; Gates, Henry Louis; Art, Corcoran Gallery of; Museum, Brooklyn (January 1990). Facing history: the Black prototype in American art, 1710–1940. Bedford Arts. pp. 11, xiii, 14. ISBN978-0-938491-38-5 . Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ Dates & Barlow, 1993.

- ^ Martindale, 1990.

- ^ Collins, 2004.

- ^ Poindexter, Smith, & Heider, 2003.

- ^ Rowley, 2003.

- ^ West, 2001.

- ^ Entman 2000.

- ^ Demby, Factor (May 22, 2013). "Where Did That Fried Chicken Stereotype Come From?". NPR.

- ^ Gilens, Martin (2000). Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy (Studies in Advice, Media, and Public Opinion). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-29365-3.

- ^ Nnedi Okorafor-Mbachu (October 25, 2004). "Stephen King's Super-Duper Magical Negroes". from StrangeHorizons.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-03 .

- ^ Susan Gonzalez (March two, 2001). "Director Fasten Lee slams 'aforementioned old' black stereotypes in today's films". YALE Bulletin & Calendar. Archived from the original on January 21, 2009. Retrieved 2006-12-03 .

- ^ a b Brookhiser, Richard (August xx, 2001). "The Numinous Negro: His importance in our lives; why he is fading". National Review . Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Jones, Trina; Norwood, Kimberly (2017). "Aggressive Encounters & White Fragility: Deconstructing the Trope of the Angry Black Woman". Iowa Police Review. 102 (v).

- ^ Collins, Patricia Hill (2000). Black Feminist Thought. Routledge. pp. 69–70. ISBN978-0-415-92483-2.

- ^ a b c Griffin, Rachel Alicia (2011). "I AM an Aroused Blackness Woman: Black Feminist Autoethnography, Vocalism, and Resistance". Women'due south Studies in Advice. 35 (2): 138–157. doi:10.1080/07491409.2012.724524. S2CID 144644154.

- ^ a b c Beauboeuf-Lafontant, Tamara (2009). Behind the Mask of the Potent Blackness Woman: Vocalism and the Embodiment of a Costly Performance . Temple Academy Printing. pp. 78–91. ISBN978-1-59213-669-eight.

- ^ a b c d e f k h i j Childs, Erica (2005). "Looking Backside the Stereotypes of the 'Angry Black Woman': An Exploration of Black Women's Responses to Interracial Relationships". Gender & Gild. 19 (4): 544–561. doi:10.1177/0891243205276755. S2CID 145239066.

- ^ "Michelle Obama: 'I'm no angry blackness woman'". BBC News. January xi, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Moody, Mia (2012). "Jezebel to Ho: An Analysis of Creative and Imaginative Shared Representations of Black Women". Journal of Research on Women and Gender.

- ^ a b c Corbin, Nichola; Smith, William; Garcia, J. Roberto (14 May 2018). "Trapped betwixt justified anger and being the strong Black woman: Blackness college women coping with racial battle fatigue at historically and predominantly White institutions". International Periodical of Qualitative Studies in Education. 31 (7): 626. doi:x.1080/09518398.2018.1468045. S2CID 150175991.

- ^ a b c Moody, Mia (Spring 2011). "A rhetorical analysis of the meaning of the 'contained adult female" (PDF). American Communication Journal. xiii (one)).

- ^ a b c Moody, Mia (Apr 1, 2011). "The pregnant of "Independent Woman" in Music". ETC.: A Review of General Semantics.

- ^ Crepeau, Richard C. (Feb 2000). Lapchick, Joe (1900-1970), basketball player and coach. American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1900111.

- ^ "Demography of Population and Housing, 2000 [Us]: Modified Race Data Summary File". 2014-09-24. doi:10.3886/icpsr13574.v1.

- ^ Njororai, Wycliffe W. Simiyu (2012). "Challenges of Being a Black Pupil Athlete on U.S. Higher Campuses" (PDF). Periodical of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics. v: 40–63. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2016. Retrieved Feb 21, 2016.

- ^ Sheldon, Jane P.; Jayaratne, Toby Epstein; Petty, Elizabeth Grand. (September 2007). "White Americans' Genetic Explanations for a Perceived Race Difference in Athleticism: The Relation to Prejudice toward and Stereotyping of Blacks" (PDF). Athletic Insight. nine (iii): 33. Retrieved Feb 21, 2016.

- ^ Wiggins, David Kenneth (1997). Glory Leap: Black Athletes in a White America . Syracuse, N. Y.: Syracuse University Press. p. 197. ISBN978-0-8156-2734-0.

- ^ Buffington, Daniel; Todd Fraley (2008). "Skill in Blackness And White: Negotiating Media Images of Race in a Sporting Context". Journal of Communication Inquiry. 32 (3): 292–310. doi:10.1177/0196859908316330. S2CID 146772218.

- ^ Hoberman, John Milton (1997). Darwin's Athletes: How Sport Has Damaged Blackness America and Preserved the Myth of Race. New York: Mariner Books. p. 146. ISBN978-0-395-82292-0.

- ^ Rock, Jeff; Perry, Westward.; Darley, John One thousand. (1997). "'White Men Can't Bound': Evidence for the Perceptual Confirmation of Racial Stereotypes Following a Basketball Game". Bones and Practical Social Psychology. xix (3): 291–306. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp1903_2.

- ^ Hall, Ronald Due east. (2001). "The Ball Bend: Calculated Racism and the Stereotype of African American Men". Journal of Black Studies. 32 (i): 104–119. doi:10.1177/002193470103200106. S2CID 145345264.

- ^ "Opinion: Black American Olympians defeat pond stereotype". Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ writer, Tetsuhiko Endo Risk sports (28 Feb 2012). "Debunking the Stereotype That Blacks Don't Swim". HuffPost . Retrieved 29 Dec 2016.

- ^ "Why Simone Manuel's Olympic gilded medal in pond matters". BBC News. 12 Baronial 2016. Retrieved 29 Dec 2016.

- ^ "Tv set Review: Blackness Ice and Other Things Y'all Don't See". Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ "Immature Harlem Athletes Are 'Cross-Checking' Hockey Stereotypes". Retrieved 29 Dec 2016.

- ^ Reporter, Travis Waldron Sports; Mail service, The Huffington (22 January 2016). "What A Generally Black Hockey Club For Kids Tells Us About The Sport'southward Future". HuffPost . Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ Standard, Pacific (nineteen June 2015). "Why the Ice Is White". Retrieved 29 Dec 2016.

- ^ Diversified, Media (17 August 2016). "It'south fourth dimension to accost the persistent stereotype that 'Black people can't swim'". Retrieved 29 Dec 2016.

- ^ "Communicable the Moving ridge: Blackness Surfing Scene Takes Off in the Rockaways". Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ "Slavery and the Making of Modernistic America (For Teachers): Historical Fiction". PBS News . Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ The Portrayal of Race, Ethnicity and Nationality in Televised International Able-bodied Events Archived July 1, 2007, at the Wayback Automobile

- ^ a b Hoberman, John Milton (November 3, 1997), Darwin'southward Athletes: How Sport Has Damaged Black America and Preserved the Myth of Race, Mariner Books, ISBN978-0-395-82292-0

- ^ "Expelling Huck Finn". jewishworldreview.com . Retrieved January 8, 2006.

- ^ Booker, Christopher Brian (2000). "I Will Article of clothing No Chain!": A Social History of African-American Males. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN978-0-275-95637-0. LCCN 99086221.

- ^ "Jackson Assails Press On Portrayal of Blacks". The New York Times. nineteen September 1985. Retrieved 2007-05-28 .

- ^ Clifford L. Alexander, Whites Only Allow Blacks Nibble at Edges of Ability, extensive quotes in the Los Angeles Times, May 23, 1991.

- ^ Crandall, David (2000-11-sixteen). "Spike Lee discusses racial stereotypes". The Johns Hopkins Newsletter. Archived from the original on 2006-09-09. Retrieved 2016-10-20 .

- ^ Robert G. Entman; Andrew Rojecki (2000). The Black Image in the White Listen . The Academy of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-21075-nine.

Entman Rojecki.

- ^ K. Sue Jewell (12 October 2012). From Mammy to Miss America and Across: Cultural Images and the Shaping of Us Social Policy. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN978-1-134-95189-5.

- ^ Yvonne D. Sims (24 August 2006). Women of Blaxploitation: How the Blackness Action Film Heroine Changed American Popular Culture. McFarland. ISBN978-0-7864-5154-viii.

- ^ Micki McElya (thirty June 2009). Clinging to Mammy: The True-blue Slave in Twentieth-Century America. Harvard University Press. p. 186. ISBN978-0-674-04079-3.

- ^ Jennifer Due east. Millard; Peter R. Grant (2006). "The Stereotypes Of Black And White Women In Fashion Mag Photographs: The Pose Of The Model And The Impression She Creates". Sex Roles. 54 (9–x): 659–673. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9032-0. ISSN 0360-0025. S2CID 144129337.

- ^ Hall, Ronald East. (September 2001). "The Ball Curve: Calculated Racism and the Stereotype of African American Men". Journal of Black Studies. 32 (1): 104–19. doi:x.1177/002193470103200106. S2CID 145345264.

- ^ Hill, Marc 50. (22 October 2003). "America'southward Mishandling of the Donovan McNabb-Blitz Limbaugh Controversy". PopMatters . Retrieved 2007-06-02 .

- ^ Sabo, Don; Sue Curry Jansen; Danny Tate; Margaret Carlisle Duncan; Susan Leggett (Nov 1995). "The Portrayal of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationality in Televised International Athletic Events". Apprentice Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-06-02 .

- ^ Grossman, Lawrence K (Jul–Aug 2001). "From bad to worse: Blackness images on "White" news". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 2007-10-14. Retrieved October seven, 2007.

- ^ Romer, Daniel; Jamieson, Kathleen H; de Coteau, Nicole J. (June 1998). "The treatment of persons of color in local goggle box news: Indigenous arraign soapbox or realistic group disharmonize?". Communication Inquiry. 25 (thirteen): 286–305. doi:10.1177/009365098025003002. S2CID 145749677.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rome, Dennis (2004). Black Demons: The Media'southward Depiction of the African American Male Criminal Stereotype. Greenwood Publishing Inc.

- ^ a b Oliver, Mary Beth (2003). "African American Men as 'Criminal and Unsafe': Implications of Media Portrayals of Crime on the 'Criminalization' of African American Men". Periodical of African American Studies. 7 (2): 3–xviii. doi:10.1007/s12111-003-1006-five. S2CID 142626192.

- ^ a b c Moody, Mia (Summer 2012). "New Media-Same Stereotypes: An Analysis of Social Media Depictions of President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama". The Journal of New Media & Culture. eight (i).

- ^ "Hispanics and Blacks Missing in Gaming Industry – New America Media". Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ Williams, Dmitri; Martins, Nicole; Consalvo, Mia; Ivory, James D. (2009). "The virtual census: representations of gender, race and age in video games". New Media & Society. eleven (v): 815–834. doi:10.1177/1461444809105354. S2CID 18036858.

- ^ Howard, Simon; Hennes, Erin P.; Sommers, Samuel R. (2021). "Stereotype Threat Among Black Men Following Exposure to Rap Music". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 12 (v): 719–730. doi:10.1177/1948550620936852. S2CID 234783670.

- ^ https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1343&context=etd[ blank URL PDF ]

- ^ https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?commodity=5251&context=masters_theses[ bare URL PDF ]

- ^ Oware, Matthew (2011). "Brotherly Love: Homosociality and Black Masculinity in Gangsta Rap Music". Journal of African American Studies. 15: 22–39. doi:10.1007/s12111-010-9123-4. S2CID 144533319.

- ^ "Black Men vs. The Stereotype of the Hyper-Masculinity vs. Hardness of Rappers | PAX".

Bibliography [edit]

- Collins, Patricia (1990). Blackness Feminist Idea . Hyman. p. fourscore. ISBN978-0-415-96472-ii.

- West, Carolyn (2008). "Mammy, Jezebel, Sapphire, and Their Homegirls: Developing an 'Oppositional Gaze' Towards the Images of Black Women". Lectures on the Psychology of Women (4).

- White, Deborah Grayness (1999). Ar'due north't I a Woman. W. Westward. Norton & Visitor. ISBN978-0-393-31481-6.

Farther reading [edit]

- Amoah, J. D. (1997). "Back on the auction block: A discussion of blackness women and pornography". National Black Law Journal. 14 (2), 204–221.

- Anderson, L. G. (1997). Mammies no more: The changing image of black women on stage and screen. Lanham, Doctor: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bogle, Donald. (1994). Toms, coons, mulattoes, mammies, and bucks: An interpretive history of Blacks in American films (New 3rd ed.). New York, NY: Continuum.

- Jewell, M.S. (1993). From mammy to Miss America and beyond: Cultural images and the shaping of U.S. social policy. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Leab, D. J. (1975/1976). From Sambo to Superspade: The black experience in motion pictures. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Visitor.

- Patricia A. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies: Black Images and Their Influence on Culture (Anchor Books, 1994).

- West, Cornell. (1995). "Mammy, Sapphire, and Jezebel: Historical images of blackness women and their implications for psychotherapy". Psychotherapy. 32(three), 458–466.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereotypes_of_African_Americans

0 Response to "Resistance Dignity and Pride African American Art in Los Angeles"

Post a Comment